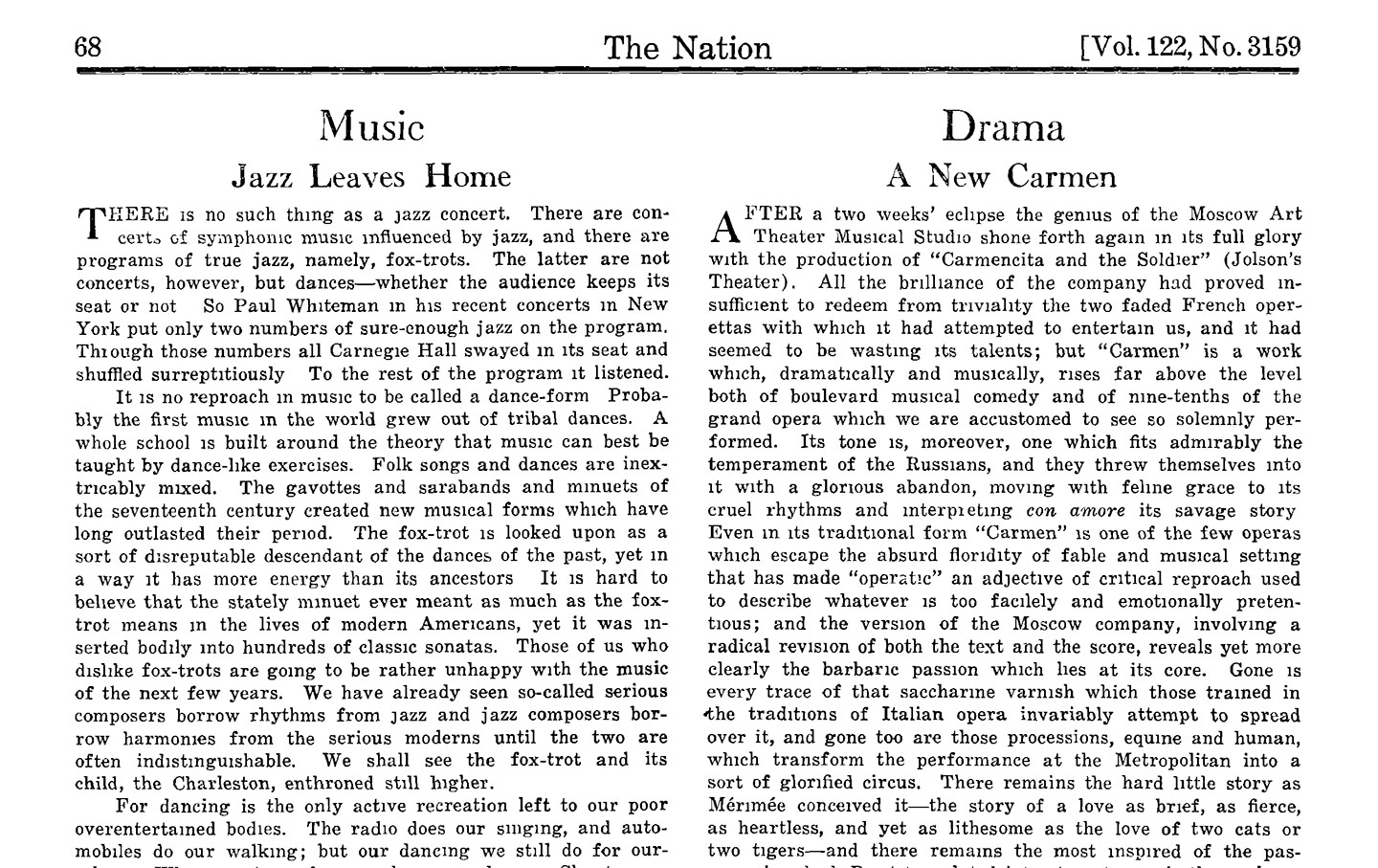

The poetry of Fady Joudah.

In his new ebook of poetry, […], the poet, translator, and ER physician explores Palestinians’ experiences of exile and displacement—and the issue of therapeutic amid the continued Nakba.

Being alone and helpless in a hospital hall —adrift between rooms, shifts, and diagnoses; stripped of 1’s property and energy, only a title amongst many others—is the closest that lots of Fady Joudah’s American readers might come to understanding the sorts of dispossession that Palestinians have skilled for practically a century. Misplaced within the labyrinthine forms of a cumbersome medical system, with few possessions and restricted company, the hallway affected person is pressured to justify himself time and again, to elucidate why he’s there, what he wants, what belongs to him. Wheeled from hall to ward to hall, he has no everlasting place to relaxation. Nurses come and go abruptly. Simply because the affected person thinks he has discovered a considerably sympathetic physician, that physician’s shift ends and one other arrives. The brand new one exhibits even much less curiosity in his illness. The affected person loses all endurance when he sees that the physician is anxious solely with treating superficial signs moderately than addressing the deeper trigger.

Joudah—an ER doctor and a translator, the kid of exiled Palestinians, and for a while now a extremely completed poet—has lengthy illuminated the methods during which this state of convalescence resonates along with his personal life and that of his household. For the Houston-based polymath, the indignities of the extractive, for-profit hospital system that he sees his sufferers caught up in function a microcosm of the state of being a refugee, of residing in exile with neither rights nor a voice—not less than not one that’s heard. As Joudah instructed the Houston Chronicle in 2008, when his first ebook of poetry, The Earth within the Attic, was printed, his poems have lengthy allowed him to carry consideration to the harrowing experiences of dislocation that he observes each in hospitals and amongst his Palestinian household and pals. “For me, being a doctor,” he added, it was unimaginable to not see that “sufferers are displaced individuals, not less than momentarily.”

In his new quantity of poetry, […], printed greater than 15 years after the primary, Joudah retains his deal with the questions of dislocation however now directs his consideration to the impossibility of therapeutic amid the protracted and ongoing Nakba. If hospitals and the Palestinian situation as soon as served as metaphors for one another, they now belong to the identical literal story: the newest part of the genocide during which Israeli warplanes and troopers goal hospitals, docs, nurses, ambulances, and Purple Crescent automobiles.

Alongside dislocation are the horrors of a battle during which the very individuals who carry therapeutic to the pained and struggling are themselves wounded or killed. Whereas “not everybody / is a doctor,” Joudah reminds us in a single poem, “in the end everybody / fails to heal.”

This grim reminder is simply one of many themes in […]. Others embody the necessity for in addition to the difficulties of mourning. “We have to differentiate / between the useless and the not right here,” Joudah writes, and but he notes that this, too, is commonly unimaginable. Many are both buried beneath the rubble or have been vaporized by the warmth produced by bombs. How can one grieve if all the normal locations of mourning, akin to grave websites, don’t exist? How can one grieve when funeral rites—which finalize the separation between the residing and the useless—can’t be held?

On this unprecedented assault on not simply the residing but additionally the useless, corpses are confiscated, graves desecrated, and full households killed off in order that there’s nobody left to mourn them. “Abruptly you / can’t discover my physique / can’t bury / what you possibly can’t discover,” Joudah writes. He reminds us that mourning is itself a luxurious that few Palestinians can afford, and that there is no such thing as a “P” in “PTSD” for a individuals repeatedly and routinely subjected to violence.

Past these keenly noticed and superbly rendered descriptions of Palestine’s tragedy, Joudah’s poems supply a startling analysis of our narrowing political horizons and even a prognosis for the way we’d act inside them. Of the numerous issues which have perished in Gaza apart from human lives—worldwide regulation, morality, the parable of the civilized West—it’s the dying of language that Joudah grieves most: “Infrequently, language dies. / It’s dying now. / Who’s alive to talk it?”

This dying of language can also be the dying of politics and the numerous avenues we now have for imagining it. If language itself is being annihilated, Joudah’s poems problem us to ask, what’s the operate of speech in a time of such untold struggling? What can language do when the sight of mutilated our bodies doesn’t jolt us into motion however as a substitute numbs us into indifference? In […], Joudah’s central and counterintuitive declare concerning the dying of language isn’t a lot concerning the absence of speech—its silencing, muzzling, or muting—however its surplus. The one who “will get to put in writing it most,” he asserts in a single poem, is the one who “will get to erase it finest.” A surfeit of phrases can work as an analgesic—whilst anesthetics are prohibited from getting into Gaza—and logorrhea, like aphasia, is a symptom of an unnameable illness that causes “ineffable struggling.”

In […], Joudah factors to different logical contortions that outline the Palestinian situation. However he does so whereas emphatically refusing to play the position of native informant. Earlier, via his English translations of Palestine’s preeminent poet, Mahmoud Darwish, Joudah helped to introduce Palestinian poetry into the canon of American letters. Now, on this time of genocide, he refuses that position altogether. “I’m not your translator,” he declares in a single poem, echoing James Baldwin’s “I’m not your Negro.” As a Palestinian writing in English, “I’m not a cultural bridge between the vanquisher and the vanquished.”

Joudah as a substitute seeks to transcend the calls for persistently made on him, whereas nonetheless attempting to show his and his individuals’s struggling. Rejecting the obscene calls for made on exhausted, grieving diasporic Palestinians to supply proof of their very humanity to deadened audiences who usually refuse to treat them as such, Joudah focuses his poems elsewhere. Though actuality “isn’t laborious to see,” he notes in a single stanza, we reside in “a world that doesn’t” seem to see it.

This latter level was pushed residence by the sight of delegates on the Democratic Nationwide Conference this previous August masking their ears to close out a recitation of the names of Palestinians killed in Gaza. And Joudah addresses and dedicates his new assortment “to the martyrs who didn’t furnish their images for his or her killers to air them on their compassionate TV. To the martyrs who didn’t communicate English. To the relatable and unrelatable, the translatable and untranslatable Palestinian flesh.” Such flesh have to be honored, even—and particularly—when it can’t be “translated” into phrases that talk to his American readership’s political issues.

In a manner, […] breaks with earlier generations of diasporic Palestinian writing and activism, particularly as exemplified by Edward Mentioned’s Orientalism. Whereas these earlier generations wagered that as a way to change the world, one needed to describe it in a different way, Joudah worries that such a redescription now not will probably be sufficient. The fantasy that if we had extra correct info and higher illustration—of larger precision and specificity, much less based mostly in crude generalizations and stereotypes—we may flatten the asymmetries of energy and impact empire’s undoing now not seems to suffice amid the ruins and rubble of Gaza.

Common

“swipe left beneath to view extra authors”Swipe →

But in Joudah’s pessimism concerning the worth of such makes an attempt, he finds the liberty to do one thing way more affecting and maybe extra tactically efficient. As an alternative of attempting to dismantle the standard myths and stereotypes that construction the imperial notion of the Palestinian individuals, he factors to the logical contradictions that underpin these concepts. For instance, he asks, “Shall I condemn myself somewhat / so that you can forgive your self / in my physique? Oh how you’re keen on my physique / my physique, my home.” By drawing on mystical tropes and aphoristic kinds, he tries to undermine the foundational antinomies of liberalism (non-public and public, enemy and good friend, non secular and secular, and so forth). And in a really totally different manner—and maybe a more practical one—he additionally tries to undermine the presuppositions that buttress a lot of the worldwide assist for Zionism and the political dispensations that allow it.

Perceiving each that liberalism’s contradictions are central to the making of the genocide and that those self same contradictions comprise the seeds of its potential unraveling, Joudah reminds us that language is endlessly promiscuous and unsettling, that it always evades the intentions of those that hope to stabilize it. For this reason, at his most good, Joudah deploys the aphorism to such startling impact: “A free coronary heart inside a caged chest is free.”

Studying […], one is struck by what number of of its strains are devoted not simply to the victims of displacement and extermination however to the perpetrators. Writing to the oppressors “who take away me from my home,” Joudah asks why they’re incapable of seeing “what’s being carried out / to me now by you.” So delusionally satisfied are they of their very own victimhood, he observes, that they’re unable to see how the poem’s dispossessed speaker is “nearer to you / than you’re to your self / and this, my enemy good friend / is the definition of distance.” Joudah doesn’t deny the sense of victimhood of those oppressors and even makes an attempt to inhabit it poetically, if solely fleetingly, permitting the antinomy between enemy and good friend to momentarily fall away. “Aggressors additionally grieve,” he reminds us in one of many many strains that straddle the sardonic and the empathetic.

However this try to inhabit the thoughts of the perpetrator isn’t carried out within the title of liberal coexistence; moderately, it’s meant to function a pointy reminder that historic victimhood doesn’t give Zionists a license to inflict cruelty on others. It additionally doesn’t give them a novel capability to grasp struggling—if something, it inures the historic victims of violence to their very own brutal acts.

Whereas there’s an intimacy to the best way that the oppressed know their oppressors, this familiarity, Joudah insists, is seldom requited. The oppressors can proceed to refuse to acknowledge not solely their victims’ humanity however how these victims are intimately tied to, and even produced by, them. In […], Joudah exhibits his readers how, on this manner, Palestinians have turn out to be the true heirs of the Holocaust. Not solely did the catastrophic dispossession that Palestinians have skilled—and proceed to expertise—within the Nakba mirror that catastrophic dispossession of the previous, nevertheless it was additionally in some methods made by it. “My disaster within the current,” Joudah writes, “continues to be not the dimensions of your previous,” but it exists nonetheless and can sooner or later, too, turn out to be part of historical past, when its magnitude shall lastly be appreciated. Even when indulging the oppressors in their very own sense of injustice, Joudah’s phrases are a surprising reminder of the asymmetries of empathy and subsequently energy that underwrite colonial relations.

A number of critics have already commented on the ineffable title, each actually and figuratively, that Joudah has chosen for […], which can also be the title of a lot of its poems. This obvious redaction of the ebook’s very title evokes the McCarthyist silencing of Palestinians in Europe and North America, and it additionally summons the redacted paperwork from the Struggle on Terror that obscured the torture of extradited prisoners in america’ navy bases and colonies.

However maybe most powerfully—and that is particularly pertinent for Joudah, who has misplaced scores of members of the family in the latest part of the genocide—the title evokes the flashing digital ellipsis that seems on cellphone screens as one waits for a response from a liked one which—within the case of those that have household or pals in Gaza—usually by no means comes. Over the previous yr, Palestinians on social media have posted screenshots of the messages they despatched that have been by no means learn, or people who have been learn however by no means obtained a solution as a result of their recipients had been killed.

I learn the title as doing one thing else, too—one thing as a lot political as poetic. The redaction and the ellipsis belong to an economic system of refusal, one which have to be understood alongside the boycott as a method that highlights liberalism’s contradictions and, in so doing, undermines them. As Joudah defined in an interview after […] was printed:

Listening to the Palestinian in English doesn’t imply that the Palestinian is at all times speaking. We additionally have to learn to pay attention in silence to the Palestinian of their silence. To date, when a Palestinian goes silent, it means they’re useless or violable, digestible, accountable for additional erasure or dispossession. English has not begun imagining the Palestinian talking, not to mention understanding Palestinian silence.

The elliptical redaction that offers the amount its title is a gesture towards the liberty to talk, sure, however maybe extra essential, additionally one looking for the liberty to be silent. Within the early weeks of October 2023, a veteran Palestinian organizer instructed me: “Now we have been combating these battles for 73 years; we’ve laid the groundwork for everybody. We’ve spoken at rallies, written articles, organized on campuses. We’re drained; we’re grieving. It’s time for the worldwide left to hold the baton for us now.”

Whereas all of us have to get higher at listening to Palestinians—to their evaluation of the previous and their analysis of the long run, to what they’ve described for many years and what they’ve cautioned us about for simply as lengthy—we should additionally watch out of our personal motivations after we “heart Palestinian voices,” lest such a requirement turn out to be a manner of evading our personal culpability. We who financially sponsor or give cowl to the genocide should additionally step into the silent hole provided by Joudah’s […] to articulate our personal topic place as perpetrators, to not simply name for Palestinian liberation however search to understand it.

“I’m eradicating me,” Joudah tells us, “from the we of you.” It’s that “we” which is left behind that should confront the ethical chasm in ourselves—dealing with our monstrous societies and states that add to the grief of the already anguished Palestinians.

That what occurs in Gaza shall decide our collective futures, wherever we might reside, is more and more apparent. How can we redistribute the battle that has fallen for much too lengthy on the struggling shoulders of Palestinians? By forcing us to take heed to the silence in […], Joudah places this query to us all. If the long run is unimaginable, the current insupportable, and the previous forbidden, then Joudah’s verses deal with us all sooner or later excellent: “I write for the long run / as a result of my current is demolished. / I fly to the long run / to retrieve my demolished current / as a legible previous.” Even of their silence, these poems current us with a deafening name to behave.

Extra from The Nation

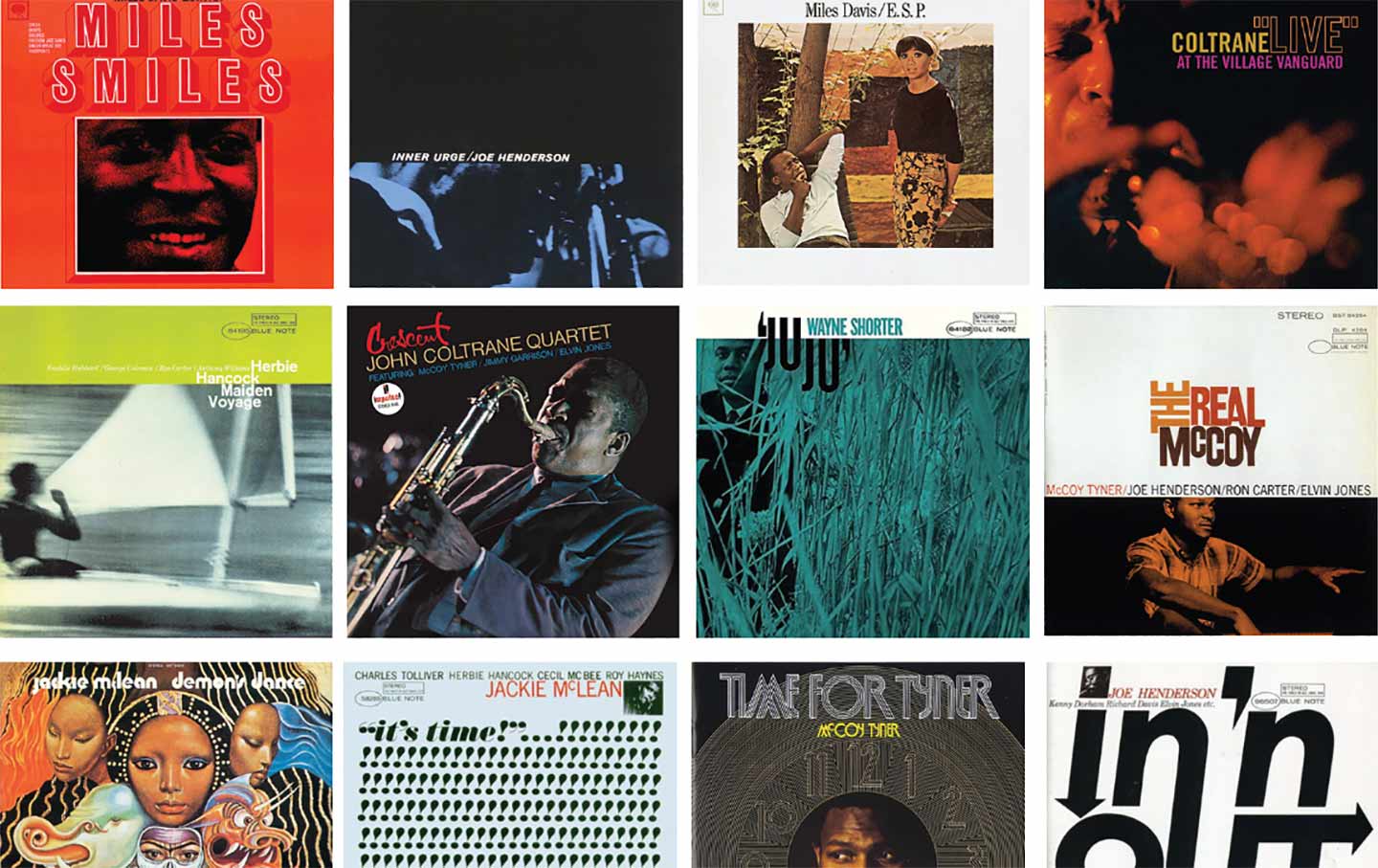

A collection of the very best recorded examples of the in any other case largely undocumented music heard in jazz golf equipment like Slugs’.

Within the late Nineteen Sixties, the recording trade misplaced curiosity in America’s best artwork type. However in a small, darkish membership on Manhattan, jazz legends have been enjoying the very best music you’ve nev…